Ajrakh: Where Earthy Dyes Meet Desert Dreams

Take a deep dive into the mystical world of Ajrakh printing, an ancient Indian art form from the deserts of Kutch and Barmer. Discover its origins, the intricate process, and the natural beauty of dyes, blocks, and age-old motifs.

INDIAN FOLK ART

Pramod Sharma

6/22/20254 min read

From Kalamkari to Ajrakh: Unfolding another masterpiece

In my previous blog, I explored the spiritual and visual depth of Kalamkari, one of India’s revered traditional art forms. Today, I am equally thrilled to take you through another remarkable journey, that of Ajrakh printing, a process just as mystical but perhaps even more complex.

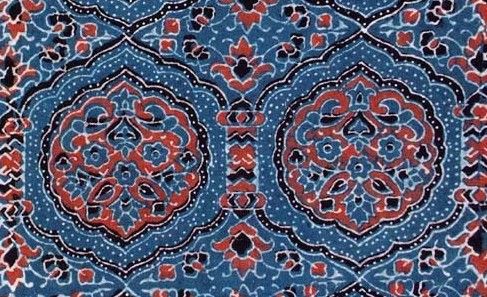

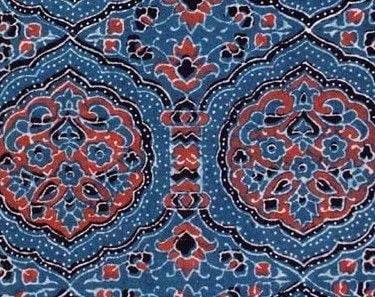

This ancient block-printing tradition, rich in symbolism and technique, is over 3,000 years old and continues to flourish. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of artisans, particularly in Kutch (Gujarat), Barmer (Rajasthan), and Sindh (Pakistan).

What does "Ajrakh" mean?

The word Ajrakh has Arabic roots, meaning "Indigo Sky". But there’s another poetic interpretation when broken down in Hindi:

Aaj (Today) + Rakh (Keep) = “Keep it today.” This suggests that the longer the fabric is kept in natural dyes, the richer and more elegant the colours become—a beautiful metaphor for patience and timelessness.

A tradition rooted in nature

Ajrakh is a resist dyeing and hand block-printing technique performed mostly on cotton, silk, and wool. No machinery is involved. Everything—right from preparing the fabric to making the dyes—is done by hand, using ingredients from the earth. The process is painstaking, yet every step adds soul to the final piece.

Ajrakhpur & Dhamadka: Hubs of heritage

Situated 15 km and 57 km from Bhuj respectively, the villages of Ajrakhpur and Dhamadka are the modern-day sanctuaries of Ajrakh. Following the devastating 2001 Gujarat earthquake, and the drying of the Saran river in 1989, the artisan community felt the need for a reliable water source, giving rise to the settlement of Ajrakhpur.

The Khatri community, with stalwarts like Dr. Ismailbhai Khatri, continues to preserve this craft. Interestingly, the art was traditionally worn by cattle herders in Sindh and Kutch, an earthy connection between utility and beauty.

The Ajrakh process: Precision, patience, and pure Craft

The process of creating authentic Ajrakh is deeply layered and demands immense discipline. From fabric preparation to dyeing, printing, and washing, each phase contributes to the final richness of the design.

Here’s a simplified look at the steps involved:

1. De-starching the cloth

White cotton cloth is soaked in a mix of castor oil , camel dung, soda ash, and hot water overnight. This breaks down starch. The process is repeated until a foamy layer forms, indicating readiness.

2. First wash

The soaked cloth is rinsed thoroughly with plain water.

3. Dyeing with Haritaki (Harde)

The cloth is dyed with Haritaki (Terminalia chebula) and then sun-dried. Longer sun exposure enhances the colour depth.

4. First resist printing

Using wooden blocks, a resist paste of gum arabic and lime (Choona in Hindi) is printed on both sides. This paste prevents certain areas from absorbing dye, leaving behind white motifs after washing.

5. Natural black printing

A black dye is made using a fermented mix of jaggery, gram flour, and rusted iron. It is kept for two weeks, then blended with tamarind seed powder, cooked into a paste, and applied using blocks.

6. Alum resist printing

A second resist paste is prepared with alum, clay, sorghum flour, and gum arabic. Sawdust is added to prevent smudging when the cloth is lifted.

7. Indigo dyeing

Indigo was once extracted from wild plants. The leaves were soaked, beaten, and left to ferment until residue formed. The resulting indigo cake was skin-safe. The cloth is dipped in the frothy dye—turning from yellow to deep blue due to oxidation.

8. Rinsing post-indigo

The cloth is washed again in plain water to remove gum, soil, and other residues.

9. Red dyeing (Alizarin & Aal)

Wherever alum resist was printed, the cloth is treated with alizarin, producing a rich red tone. Aal leaves (Morinda citrifolia) and madder root give the characteristic red and terracotta hues of Ajrakh.

The language of patterns

Ajrakh isn’t just about colours—it speaks through symbols. Its motifs are drawn from nature and philosophy, each carrying cultural meaning. Here are a few:

Kakar – Symbolises clouds, representing life-giving rain

Mor Peech – Inspired by the peacock’s feathers

Miphudi – Depicts raindrop bubbles

Champakali – Stylised version of the Champak flower bud

Kharak – Represents date palm trees, common in the desert

Riyal Patterns – Intricate geometrical floral patterns often seen in coins or tile art

These designs are engraved onto hand-carved teak wood blocks (Saagwan in Hindi)—each block an artwork in itself.

A myriad of sustainability

What makes Ajrakh more than just beautiful is its eco-conscious essence. Every material—be it the dyes from henna, rhubarb root, turmeric, sappan wood, or the binders like gum arabic—is natural. The process ensures the fabric is not only skin-friendly, but also biodegradable.

Why Ajrakh still matters today

In an age of mass production and synthetic quick fixes, Ajrakh stands as a reminder of patience, craft, and respect for nature. Every motif tells a story. Every dye has a purpose. And every artisan passes down knowledge that’s centuries old. In 2025, Ajrakh is not just surviving, it’s thriving, proudly adapting to modern platforms while holding on to its roots. This isn’t just an ancient textile tradition tucked away in rural India; it’s a style statement, a story, and a symbol of sustainable fashion.

Take for example the Times Fashion Week held in April 2025 in Mumbai, where designer Nitya Bajaj showcased Ajrakh-inspired silhouettes. Actress Mouni Roy turned heads in a stunning black Ajrakh fish-cut lehenga saree, proof that this age-old art still resonates on contemporary ramps.

Beyond fashion runways, Ajrakh has quite literally taken flight. The tail of Air India Express aircraft (Reg: VT-ATD) proudly features an Ajrakh block pattern, soaring through the skies as a tribute to India’s artistic legacy. It’s a powerful reminder that our traditions deserve visibility—not just in museums, but also in motion.

As more designers, platforms, and even airlines embrace indigenous crafts, Ajrakh continues to inspire a new generation of creators and consumers. And its growing popularity reinforces one key truth: heritage doesn’t have to be frozen in time. It can be worn, flown, and reimagined. I’m heading to Bhuj soon. When are you planning to explore Ajrakhpur?

Image Source: Pinterest

© 2025. Pramod's Art Studio All rights reserved. Registered MSME – Udyam No: UDYAM-TS-20-0133833